Let’s face it, pretty much every rebuild starts the same way. Flip the ratchet to “undo” grab a handful of spanners and start ripping the thing apart.

Actually, now I think about it, it’s a bit more than a handful of spanners. Somewhere in the job you’re going to either need, or find the job much easier with, one or more special tools.

I seem to remember as a callow and impecunious teenager managing to rebuild a C15 and a Cub without having any, but it usually involves a fair amount of swearing, wasted time and, very probably, damage to components.

It’s a matter of choice how far you go and where you get them. Most are relatively easy to buy nowadays and many you can make yourself, so it’s a toss up between whether it’s cheaper/easier to make, buy or adapt something else.

I was a bit lazy on this job and bought two. One was a clutch puller and the other a crankshaft pusher/puller. I could have made both, but it wouldn’t have saved a lot of money, by the time I’d bought materials (none of which I had in my usually reliable scrap bin) and would have taken a fair bit of time and effort.

In short, make sure you’ve got what you need up front, as it’s really frustrating losing a valuable weekend because you can’t get the right tool until Wednesday.

Being the beginning of the job it’s easy to be overenthusiastic and believe that you’ll remember where everything went, not to mention what it was, because when you’re looking at it in situ, it’s blindingly bleedin’ obvious. I promise, that in a few months’ time it won’t be, or at least it never is for me. So gather your tags, boxes, bags, pens and camera/phone and document the thing to death. It’s always a good plan.

Starting at the top I whipped off the push rod inspection cover, just for a quick look. It’s worth noting which push rod is which (red for exhaust in this case) then it’s off with the rocker box.

A quick look reveals a bit of wear on the tappet adjusters, but nothing horrid. They’ll be replaced anyway.

Now, we all know that in every such job there is a stud which decides to come out with the nut. In this case (naturally) it had to be the one stud that didn’t have enough clearance to come out.

One answer would have been to ease the head off a bit at a time, but it would still have been stuck there, because it can’t come out of the head upover. I figured it was better to sort it now than end up with it stuck in the head, so I flooded it with easing oil, wound it out until it was jammed against the rocker box stud and that held it enough to free the nut.

Take note, you need a bit of a sympathetic hand to do this, there’s always the possibility, if you rive at it hard enough, to strip the threads in the crank case, or possibly crack the head where the rocker box stud is.

Once off, the head didn’t look bad at all for such an old bike…

and neither did the piston crown.

One could easily suspect a top end rebuild in it’s recent history.

The barrel follows pretty naturally, then the problem of the piston arrives. By all means have a gentle shove at the gudgeon pin, but if it comes out it’s knackered. It should be a very tight fit. Oh yes, don’t forget to take the circlips out and don’t even think about re-using them.

The answer lies in the kitchen. Moving with the stealth of a cat burglar the intrepid spanner spinner needs to stick the kettle on and, without making any sounds that could give him away… steal a tea towel!

Wrap the tea towel (not the souvenir Charles and Dianna one) around the piston and pour a kettle full of boiling water over it. The tea towel will retain the hot water for long enough to expand the piston and the gudgeon pin should just push out, or at least require only a very gentle tap. It did too! You’ll notice from the pictures that the rotating engine stand really does make these tasks easier.

All these bits, by the way, are making their way into takeaway boxes and labelled plastic bags, as I remove them, so there are no piles on the bench.

I can never resist giving the con rod a bit of a wiggle about at this point. You’ll be able to move it side to side a bit, but it should have no detectable up and down play at all. In practice, it’s quite hard to tell the two apart until you get used to doing it. One trick is to hold the con rod tightly in one hand and pull it up as hard as you can (at top dead centre) then, with the other hand, clout it quite hard on the top. If there’s play you’ll usually hear a “clonk”. That test works even better with the crankshaft out and dangling off the rod.

With the top end duly packed away, my attention turned to the primary drive side, primarily because the engine happened to be that way round.

I’m a big fan of the traditional “cornflake box” method of storing case fixings. Simply draw the case on a bit of cardboard, poke some holes in and stick the bolts in the appropriate holes as you take them out. The takeaway box stops them slipping out.

Incidentally, I believe in doing this even if you’re planning to replace them with a nice shiny set of stainless allen head bolts. The main reason being that you can still see which ones are which length, without getting all but one of them in and then finding out it’s too long for the only hole you have left.

While we’re here, I think the subject of nice stainless bolts is worth a bit of a digression, though really, I suppose it should wait for the rebuild bit.

It’s very easy to assume that replacing as many fasteners as possible with new stainless ones is the best way to go. Sometimes it is, but in each individual case you really need to consider the side effects.

For primary case bolts I almost certainly will go to stainless allen heads, but there are issues to be considered.

The first is that one can exert far more torque on an allen bolt than one can with a cross head screwdriver. This can have one or both of two different effects.

The first and most obvious, is the possibility of stripping the threads in the aluminium case. Nuff said on that.

The second, and much less obvious, is that it can cause oil leaks. Yes, you read that right, tightening the case too much, even perfectly evenly, can make it leak. I really wish I’d known that all those years ago when I had my first C15 and couldn’t for the life of me figure out how it kept getting leakier the more I tightened it up.

It works like this…

Once you get past a certain tension on the bolt, it not only pulls the outer case down (or “in” if you prefer) but also pulls the inner case up, or out. The result is a little volcano shaped mound around the hole, where the threads have deformed the case.

Much exaggerated it would look something like this. If you have an old leaky case, try taping a bit of fine wet and dry to a sheet of flat glass then rub the gasket surface on it a little bit. You may well see such mounds come up clean before it gets down to the flat surface. In fact, if you do, keep going until it’s flat again!

Instinctively, I wouldn’t have thought it would be pronounced enough to overcome the give of the gasket, but I’ve seen it a few times and it certainly can. I suppose logically, this is a BSA and, as such, doesn’t need a second invitation to spring a leak.

And, just in case you don’t believe me, take a look at the holes where the carburettor studs went.

Another potential problem with stainless bolts (though less so on the primary case than in some other applications, particularly cylinder head bolts) is that they’re nice and shiny. I know, that’s largely the point, but shiny is also slippery and stainless steel bolts are much more prone to vibrating loose than ordinary ones. Nowadays, the wonders of Locktite will largely mitigate the problem in most cases, but you still need to keep in mind that it’s there and needs to be dealt with.

So, where was I? Oh yes, the primary side.

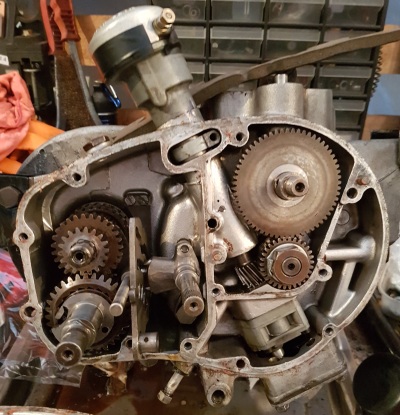

The first thing I noticed, here, was just how clean everything was. It’s a theme that continued throughout the engine strip and has me strongly suspecting a recent rebuild, but the chap I bought it off didn’t really know it’s history, so I’m not going to trust anything. Anyway, a bad rebuild can be worse than none, though I’ve no reason to suspect bodgery here at all.

The alternator stator is just three bolts then you reach the big nut, on the end of the crank shaft, that holds the rotor on. There’s a tab washer to flatten (I still do it gently with a screwdriver and a hammer) then there are two problems. Firstly, it’s ruddy tight and, secondly, the crank shaft goes round and round rather easily.

The second problem is solved by putting a couple of bits of wood over the crank case throat, to protect it, then sticking a big bar, wrapped in gaffer tape, through the little end. The reason it’s a big bar is to prevent it putting a groove in the little end bearing and the gaffer tape is to protect it’s surface.

for the tightness, I use a huge breaker bar. Mine’s nigh on three feet long. Now this will allow far more torque than I’d really like to apply to any bit of BSA, but it allows it to be applied very easily, and that’s important. If you have to clobber the bar, or jerk it, or lean on it, then you’re not really in control of how much torque you’re applying to the job. A nice, gently increasing pressure allows you to keep control and you’re far less likely to break something, unless you’re a ham fisted idiot, of course. In general, I really don’t like hitting things, well not motorcycles anyway.

Once that’s out of the way, the primary chain tensioner just pulls off. A label with string on is good for keeping the spacers in the right order.

Then it’s clutch time!

Start with the biggest screwdriver you can find to remove the springs. They’re not horribly tight and seldom go flying about the place. You’ll notice that one of mine was a wee bit mangled. Again, they’ll be replaced.

Once that’s done the cover comes straight off and you can fernagle the plates out. They never give up easily. I angle the engine downover a bit and use two small screwdrivers, at opposite sides of the plate to encourage them out.

Then it’s the other big nut, which gets exactly the same treatment as the last one. Looks like someone’s had a hammer and chisel to it!

The exception to my dislike of hitting motorcycles is when they have machine screws or slot or cross headed bolts in them. I virtually always use an impact driver. Partially because it drastically reduces the chances of mangling the head and partially because mine actually has far better tips than any of my manual screwdrivers.

In this case I was applying it to the four screws that hold the clutch centre in, none of which were a problem.

The thrust washer and clutch rod come out easily and then I allowed myself the luxury of using my store-bought extractor to remove the clutch centre.

Then you can pull off both ends of the primary drive, but be ready to catch all the rollers from behind the clutch.

The job is definitely underway!